Houston Center of Photography: THE VANGUARD,Rebel Girl, and Soft Heat…and a conversation with Anne Massoni

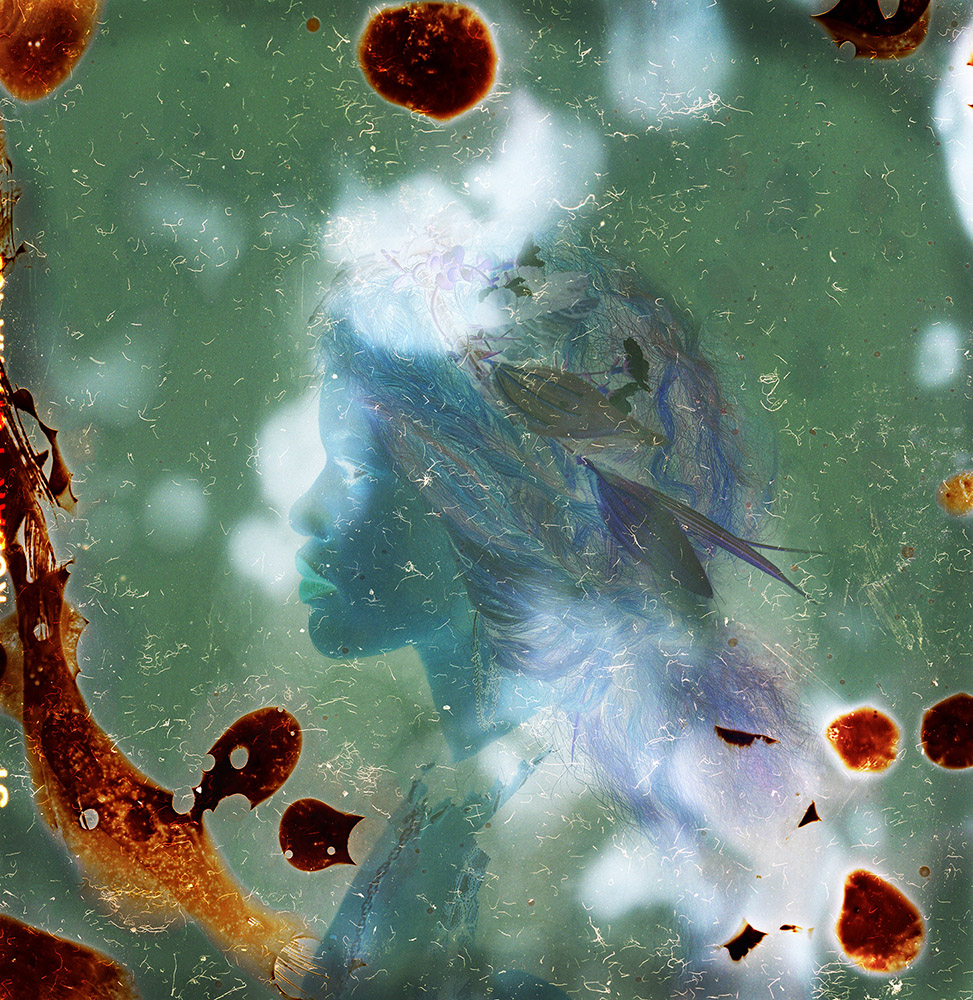

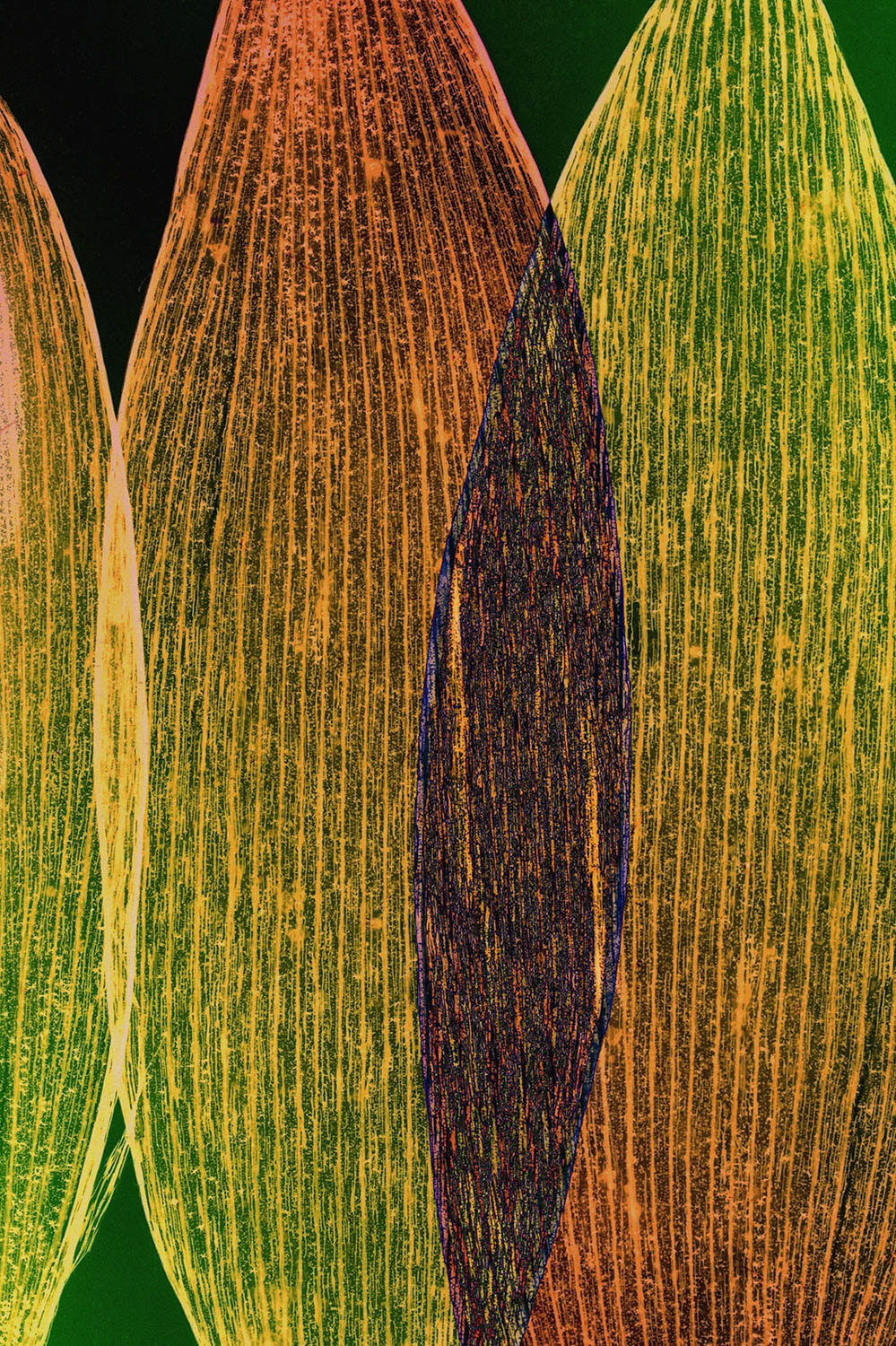

©Dornith Doherty, Intersect, 2024 (courtesy of Dornith Doherty and Moody Gallery),from the exhibition, THE VANGUARD

Today we feature three exhibitions that open tonight at the Houston Center for Photography (HCP): THE VANGUARD, Rebel Girl, and Soft Heat, celebrating women photographers But we also are in conversation with HCP’s new Executive Director, Anne Leighton Massoni. I first met Anne a few years back through my teaching with ICP and was excited to now see her spearheading this prestigious organization. Scroll to the end for the interview.

Women have long shaped the language of photography, bringing vision and creative depth to the medium, often without equal recognition. Over the past two decades, women in the field have achieved greater visibility and influence, redefining the profession and institutional standards. Trailblazing organizations such as Houston Center for Photography (HCP) have been vital to this progress. For 45 years, HCP has consistently honored, supported, and advanced the work of women, ensuring their voices are firmly embedded in the contemporary photographic landscape. With women shaping its vision from the very beginning of its formation, HCP’s commitment to equity remains a defining part of its legacy.

Exhibition Related Dates:

Rebel Girl and THE VANGUARD: March 12 2026 – May 24, 2026 Opening Reception (Rebel Girl, THE VANGUARD, and soft heat): March 12, 2026 from 6:15 – 8:00 PM

Artist Panel Conversation (Rebel Girl and THE VANGUARD): March 12, 2026 from 5:30 – 6:15 PM

soft heat by Jamie Robertson: March 12 2026 – April 12, 2026

Artist Talk (soft heat by Jamie Robertson): March 18, 2026 from 6:30 to 8 PM

Curatorial Walkthrough (Rebel Girl, THE VANGUARD, and soft heat): May 2nd, 2026 from 10:30 AM – 12 PM

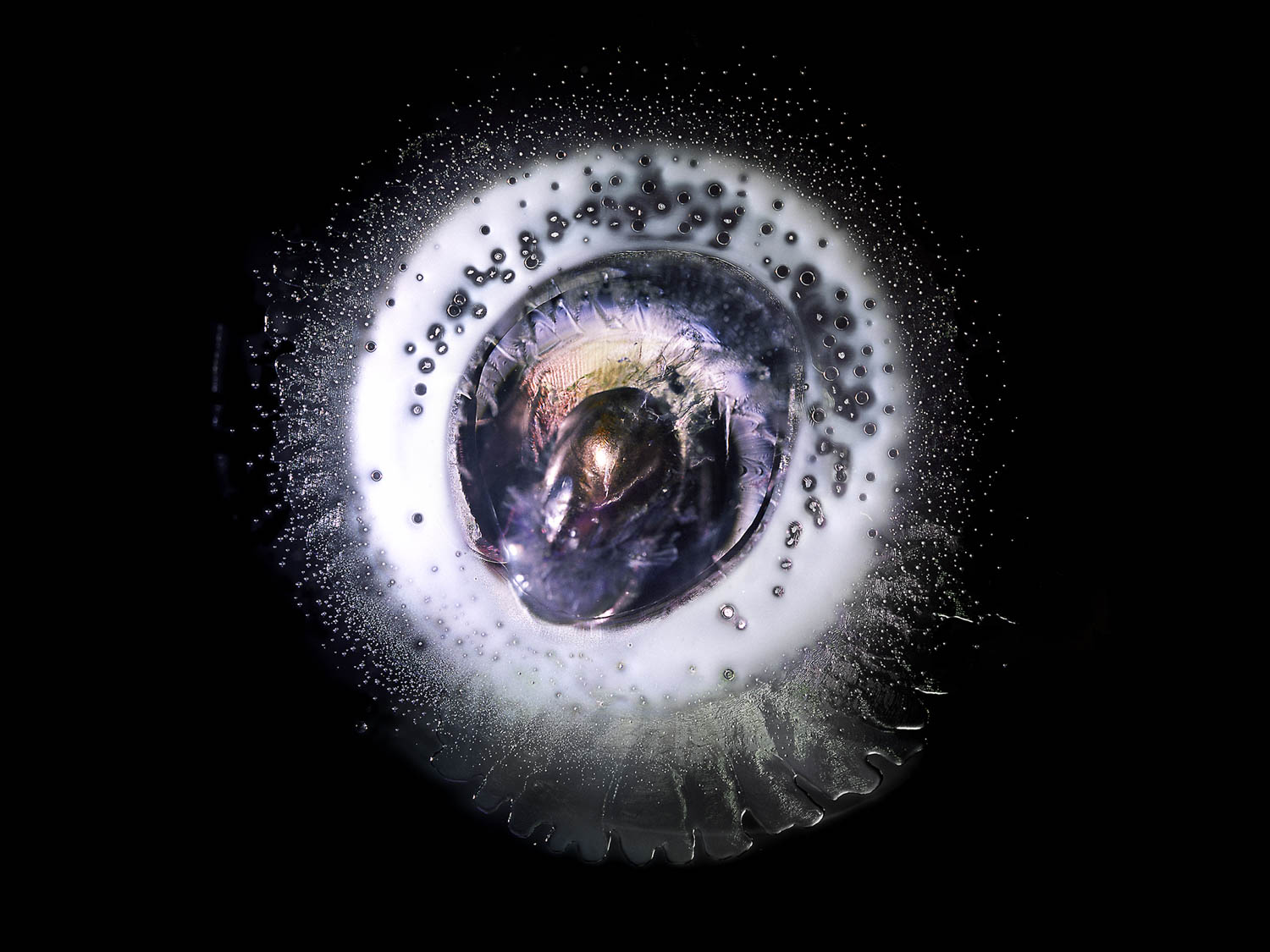

THE VANGUARD is a journey into HCP’s archives, featuring Yolanda Andrade, Bennie Flores Ansell, Deborah Bay, Gay Block, Carol Crow, Dornith Doherty, Susan Dunkerley Maguire, Melanie Friend, Susan kae Grant, Mary Margaret Hansen and Patsy Cravens, Graciela Iturbide, Priya Kambli, Jean Karotkin, An-My Lê, Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, Kenda North, Aline Smithson, Maggie Taylor, Wendy Watriss, and Carrie Mae Weems.

©Deborah Bay, 9mm Uzi 2, 2014 (Courtesy of artist), from The Big Bang series, from the exhibition, THE VANGUARD

Featuring 20 photographers, THE VANGUARD affirms HCP’s long-standing dedication to platforming women. With legacies that continue to resonate, their careers have laid the groundwork for the contemporary practices of women exhibited at HCP today.

For an expanded curatorial statement for THE VANGUARD visit the exhibition webpage.

©Maggie Taylor, Girl with a Bee Dress , 2004 (Courtesy of Catherine Coutuier Gallery), from the exhibition THE VANGUARD

©Mary Margaret Hansen and Patsy Cravens, Blowin’ in the Wind, 1980 (Courtesy of Heidi Vaughan Fine Art), from the exhibition THE VANGUARD

©Susan kae Grant, Nocturnal Visit #066 2012 (Courtesy of Joy Simpson), from Night Journey, from the exhibition THE VANGUARD

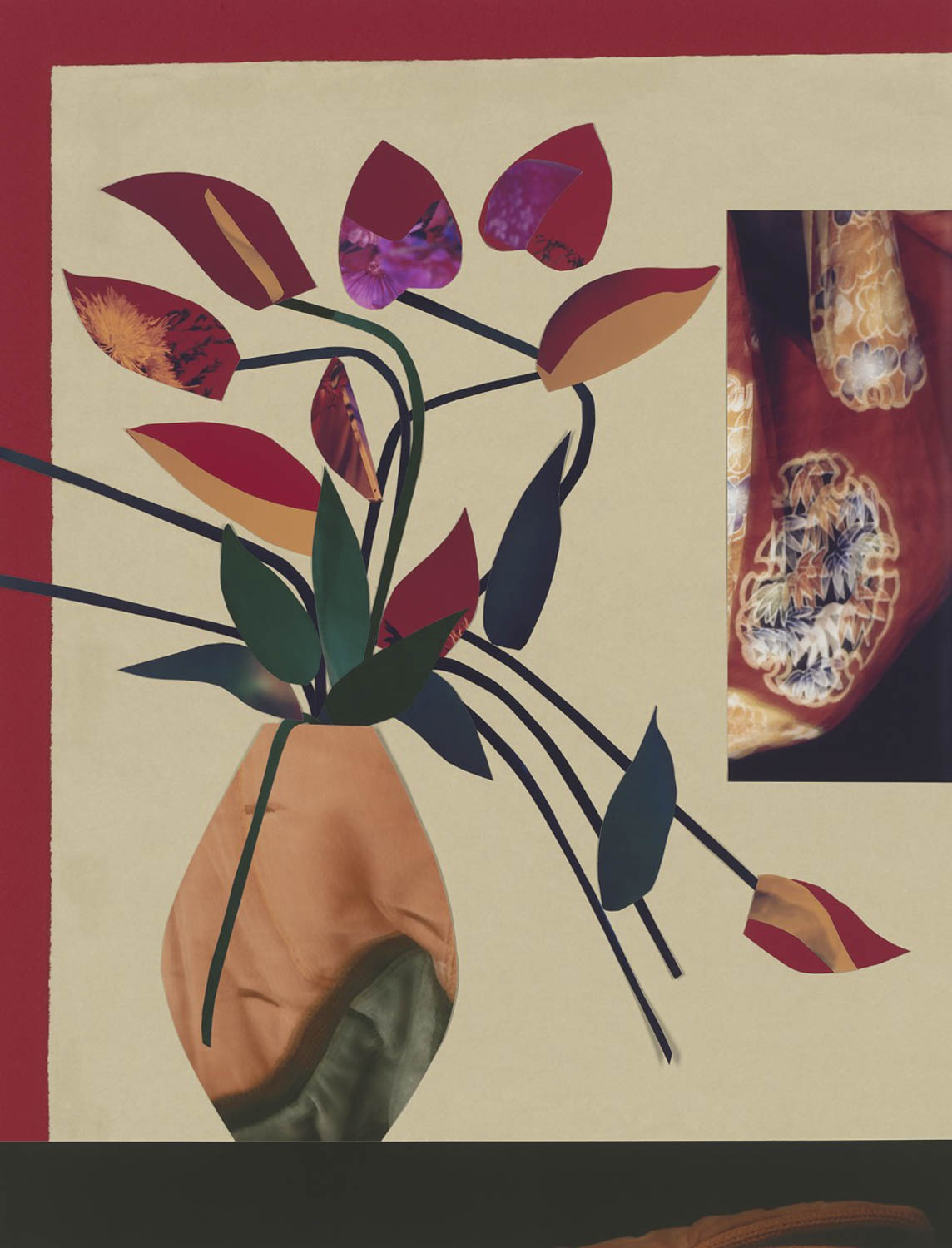

A companion exhibition, Rebel Girl, celebrates this legacy by highlighting both HCP’s historical commitment to championing women’s photographic careers and the work of contemporary photographers exploring the complexities of female identity.

Rebel Girl features:

- Luisa Dörr: Dörr’s series Imilla documents female skater culture in Bolivia, where women wearing traditional pollera skirts bridge cultural heritage and modern subculture.

©Luisa Dörr, Joselin Brenda Mamani tinta (27) and Lucia Rosmeri tinta Quispe (46) Brenda and her mother are considered Pollera women from a different ethny called Aymara from La Paz. Brenda started skateboarding 6 years ago and felt that this activity could give her direction, something to learn that would stimulate her to drop her fears and get out of her comfort zone. She says – “It makes me feel capable because I can break my own limits and I can dare to do things that I have never thought about, and like this I can get over my daily fear. For her skateboarding in Pollera outfits means a challenge by itself because it is very hard to skateboard wearing a voluminous skirt but she knows that perseverance and practice will help and she has been improving her skills. For her this activity represents her roots, the place she comes from and who she is. From the exhibition Rebel Girl

- Selina Román: Román’s abstracted self-portraiture uses brightly colored spandex to transform the natural curves of her body into geometric color fields, playing with form and calling us to question “excess” in the aptly titled series XS.

- Jo Ann Chaus: In Conversations with Myself, Chaus reflects on the mid-century ideals of femininity that shaped her upbringing, staging their tensions against the lived reality of navigating an aging body in an era of body positivity.

The 3rd Exhibition, soft heat, by Jamie Robertson, is a photographic study of wetlands in the Southern United States through black and white infrared film photography.

Falling out of the visible spectrum of light, infrared images visually shift our understanding of what is seen allowing the environment’s memory or ‘specter’ to be realized. What can a swamp remember? Does the Great Dismal Swamp remember George Washington’s “triumphant” trek into its’ interior? Does it remember the hundreds of Maroons who called it home? This work is a continuation of my exploration of swamps and the space they hold in American society. Emerging from crowd-sourced data, the title soft heat embodies the qualities of the landscape and the infrared image. The swamp’s soft, watery environment is rendered as thermal ‘heat’ in a soft, spectral light, challenging harsh attitudes to uncover the environment’s delicate strength.

My creative practice explores the environment of the American South and its relationship to Blackness. Deep in Southern soil lies a rich history of Black defiance. Through research, writing, photography, and video art, my work excavates this history, contending with the vilified and monolithic narrative of the Southern United States. Using a Black Feminist Hauntological and Eco-Womanist lens, I balance this layered and sometimes untold history while honoring the land. I approach image-making fluidly, oscillating between analog and digital processes. I utilize text, archival images, and found imagery as materials and companions to my work to oppose the hierarchy of high and low culture. Currently, I am interested in black and white infrared film as a poetic means of seeing beyond human sight, revealing the “spectral” presence that haunts the Southern landscape.

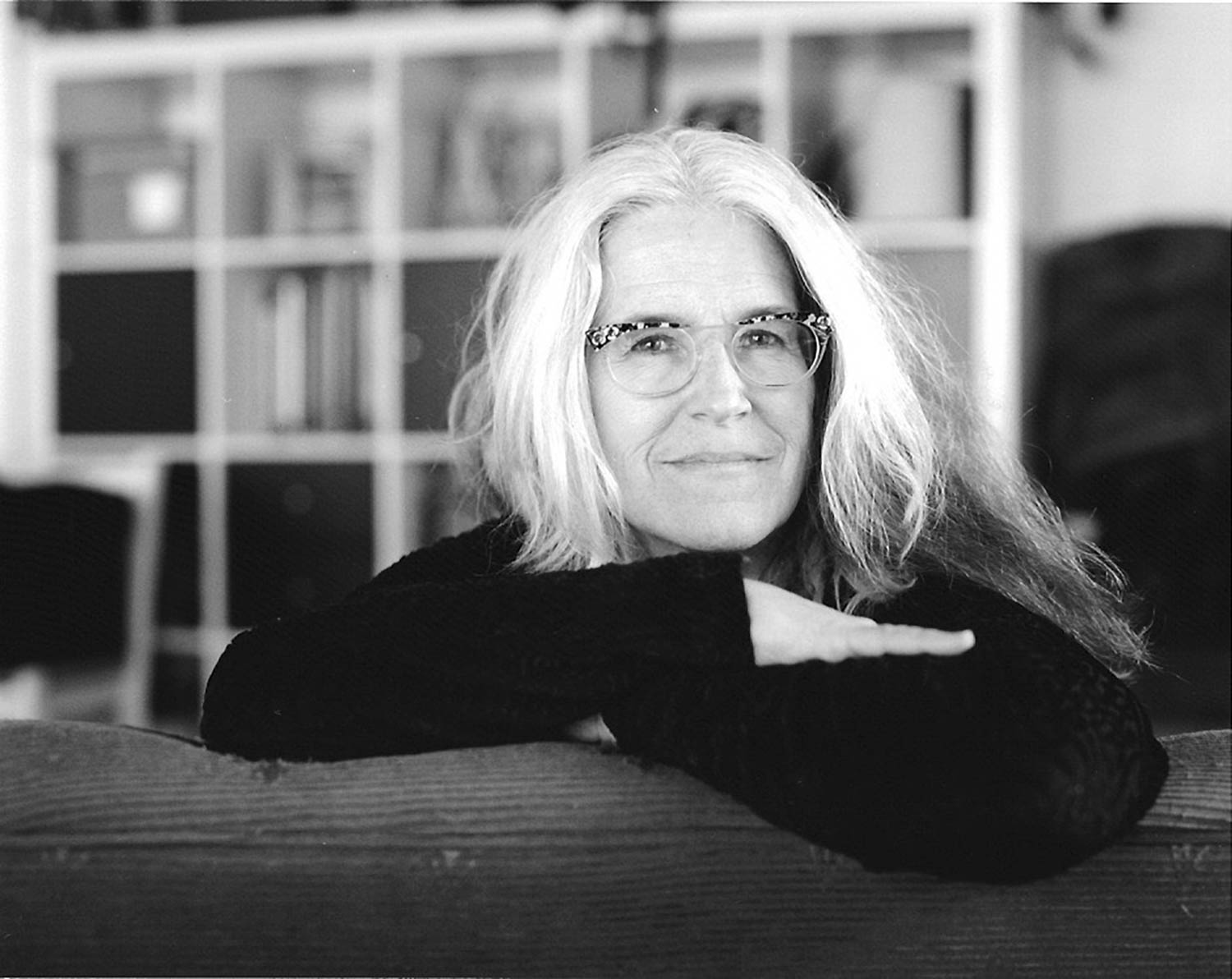

Conversation with HCP Executive Director and Curator, Anne Leighton Massoni

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography….

I grew up in Washington, DC and later on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. I was a curious kid with an eagerness to experience the world – over time, the camera would become that vehicle for exploration. In 1989, I traveled to the Soviet Union as a student ambassador with People to People, bringing a small point-and-shoot camera with me. I photographed everything. One image—taken on an airport tarmac after weeks of travel—was selected 24 years later for the exhibition Early Works about the moment photographers fell in love with the medium. Its strangeness and open-ended storytelling still reflects my artistic approach.

At 17, I got my first SLR and taught myself to use it, learning through experience and the books my dad shared rather than formal classes, he was a skilled amateur photographer. In high school and throughout college, I worked for Constance Stuart Larrabee, the first female South African war correspondent, assisting with archiving, editing, and exhibition preparation. Her mentorship deeply shaped my understanding of composition and form.

I earned my undergraduate degree in Anthropology and Photography from Connecticut College and completed my MFA in photography at Ohio University. I entered my first full-time role as a professor less than 2 months after defending my masters thesis – I’ve spent the better part of 30 years working professionally in the photography industry from practitioner to educator as well as an administrator and curator.

After decades in academia in New York , what brought you to the Houston Center of Photography in Texas?

And not just NY! I spent 22 years in academia and taught at a myriad of schools including Cornell University, University of the Arts (UArts), and the International Center of Photography (ICP) to name just a few. I spent more than a decade of those years in administrative roles. In order to share what brought me to HCP, I have to first share that I left the UArts in Philadelphia in 2020 to take on the role of Dean & Managing Director of Education at ICP in New York City because I wanted to transition out of a traditional higher education environment. Things were changing in higher education and I wanted more freedom to address new and alternative modalities of learning. I knew I wanted to stay in the world of photography, but I wanted to have a more substantial community impact – turning to one of our photo centers was the final pivot and I was thrilled when the Houston Center for Photography (HCP) offered me the role of Executive Director & Curator.

What excites you about this new role, as Executive Director & Curator?

What excites me most is the collaborative spirit of our team and the impact of our work at the Houston Center for Photography. As one of the few dedicated photo centers in the country, HCP has spent 45 years fostering a multigenerational community. We believe every reason to be in the classroom has merit, which is why our educational programming—led by Natan Dvir—ranges from iPhone and AI photography to our newly launched certificate programs.

Our community engagement programming has also reached new heights. Under Lindsay Sparagana’s leadership, we’ve established nearly 40 partnerships, bringing arts programming to K-12 students throughout the Houston metro area. We’ve also launched a multi-track high school program to bridge the gap between current passion and future profession, offering pathways in fine art, curation, and business. And in exhibitions, in addition to our annual programming, we recently dedicated gallery space and honoraria specifically to Houstonian photographers for the purposes of solo exhibitions, ensuring that local talent has a visible, supported platform within their own city.

While my role has shifted toward fundraising and curation, I am energized by the passion of our “small but mighty” staff, including Director of Operations Theresa Marshall and Exhibitions & Programs Coordinator Areli Navarro Magallón who make it possible for me to fulfill those roles as Executive Director and Curator. Supported by a dedicated board and the vibrant Houston art scene, HCP is playing a vital role in photography.

Tell us about your inspiration for The Vanguard Exhibition.

The start of 2026 marked the Houston Center for Photography’s 45th anniversary. As Executive Director and Curator, curating the group exhibition The Vanguard was deeply personal and especially timely. I joined HCP in 2023, having known the organization since my time in graduate school (1998–2000). First through its former publication SPOT, and later by following the curatorial careers of previous Executive Directors and Curators Madeline Yale Preston and Bevin Bering Dubrowski, HCP was on my radar long before I came to my present stewardship of it.

Not only were many of HCP’s founding members women, but as a member-run organization, they had meaningful voices in shaping the center’s early direction. Add to this the extraordinary leadership of the esteemed Anne Wilkes Tucker, who was deeply involved in curatorial decisions during HCP’s earliest years, and it is clear why HCP became a pioneer among photo centers..

HCP was instrumental in introducing me to a wide array of women photographers at a time when my formal education had overlooked them. In 2001, as HCP was turning 20, I found myself on the precipice of my professional career in academia and realized this was the pivotal moment for me to play a part in rectifying these institutional erasures. By ensuring that students and emerging artists had the opportunity to encounter and be inspired by extraordinary women in the field of photography, HCP’s enduring legacy moved through me long before I ever set foot in Houston. Years later, I would come to understand how profoundly that legacy has shaped my own trajectory, eventually leading me to HCP.

What better way to celebrate this legacy and mark our 45th anniversary than by acknowledging the very people who started it all—both for HCP and for myself. Curating THE VANGUARD has been a rich journey through HCP’s archives. After sifting through hundreds of women exhibited during the center’s first 20 years, I ultimately selected 20 artists for the exhibition. Each woman falls into one of three curatorial categories: artists I discovered in the early 2000s thanks to HCP, artists with whom I have had the honor of sharing a curatorial relationship, and artists I encountered upon arriving in Houston whom I regretted not knowing sooner.

With these categories in mind, I have paired each work with a personal anecdote on extended wall labels, inviting viewers to engage with both the artists’ practices and my own journey with HCP.

The Vanguard includes: Yolanda Andrade, Bennie Flores Ansell, Deborah Bay, Gay Block, Carol Crow, Dornith Doherty, Susan Dunkerley, Melanie Friend, Susan kae Grant, Mary Margaret Hansen / Patsy Cravens, Graciela Iturbide, Priya Kambli, Jean Karotkin, An-My Lê, Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, Kenda North, Aline Smithson, Maggie Taylor, Wendy Watriss, and Carrie Mae Weems.

The Vanguard is a companion exhibition to Rebel Girl that celebrates contemporary photographers engaging with the many dimensions of female identity. Their work highlights the diversity of experience, questioning stereotypes and illuminating the evolving roles and perceptions of women today. Rebel Girl features

- Luisa Dörr: Dörr’s series Imilla documents female skater culture in Bolivia, where women wearing traditional pollera skirts bridge cultural heritage and modern subculture.

- Selina Román: Román’s abstracted self-portraiture uses brightly colored spandex to transform the natural curves of her body into geometric color fields, playing with form and calling us to question “excess” in the aptly titled series XS.

- Jo Ann Chaus: In Conversations with Myself, Chaus reflects on the mid-century ideals of femininity that shaped her upbringing, staging their tensions against the lived reality of navigating an aging body in an era of body positivity.

Together, these artists challenge convention while celebrating alternative narratives of femininity. Our standard image of a skater rarely includes traditional Bolivian attire, expectations of the female form continue to be bound by narrow standards of size, and cultural views of aging and beauty often marginalize women as they grow older. Each artist foregrounds these exceptions, normalizes their existence, and invites us to reconsider womanhood across its unfolding stages, from youthful rebellion to mature reflection.

What’s on the horizon for the Organization?

HCP is moving!

After an incredible 40-plus years at our beloved location on 1441 West Alabama Street, the Houston Center for Photography (HCP) has reached a pivotal moment and is embarking on a journey to find a new home.

This decision, while marking the end of an era, is driven by a clear vision for HCP’s growth and long-term sustainability. Primarily, we have come to realize that our current facilities no longer provide the space necessary to fully realize the scale of our ambitions and programs. Additionally, the terms of our long-standing lease no longer align with the evolving needs of our landlord. HCP engaged its members and the community at large in a series of town hall meetings and learned that collaborative, engagement, and creative space was critical. For that reason, our new home will feature a makerspace, darkroom, and production facilities; secondary and adult education space, drop-in safe spaces, and a dedicated student gallery; an expanded library; and a robust residency program.

Importantly, we heard the desire to remain within the Museum District and Montrose area of Houston, a commitment we have taken to heart. The Board of Directors led a diligent search with the expert guidance and assistance of Savills and secured a remarkable historic property located in close proximity to the MFAH, CAMH, and the light rail. Beyond location alone, this new home presents exciting opportunities for deeper collaborations with our esteemed sister institutions and ensures convenient access for our visitors and the broader community.

This is a truly transformative moment for the Houston Center for Photography, and we are incredibly enthusiastic about the opportunities this new chapter will bring. This move will enable us to better serve the Houston photography community, expand our reach, and further solidify our position as a leading institution dedicated to the art of photography.

Should Lenscratch’s readership be interested in learning more about our new home and Capital Campaign – I’d welcome the opportunity to share more information!

Thank you Anne! So excited for the future of HCP!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Houston Center of Photography: THE VANGUARD,Rebel Girl, and Soft Heat…and a conversation with Anne MassoniMarch 12th, 2026

-

A Collaborative Photographic Exhibition by Heather and Ben Mattera: Weight of It AllMarch 7th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Landscape ReEnvisioned Exhibition At the Monterey Museum of ArtFebruary 26th, 2026

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026