This week, Lenscratch explores the work of 4 fathers interpreting life with their Autistic sons…

Charles Mintz considers photography his third career, a career that has moved into intensely personal arenas, allowing him to not only mine his life for visual exploration, but consider his world with thoughtful analysis. I am featuring two of his series, The Album Project, a collaborative effort with his Autistic son Isaac, and Every Place I Have Ever Lived, an untraditional look at interpreting home. The Album Project has accompanying videos, and a book is available for purchase here.

Chuck studied photography at Maine Photographic Workshop, Parsons School of Design, International Center for Photography, Lakeland Community College and Cuyahoga Community College. He has both bachelors and master of science degrees in electrical engineering and has studied Japanese. He is a director of ICA – Art Conservation in Cleveland, OH and the Cleveland Museum of Art – Friends of Photography and is a Life Director at Jewish Family Services of Cleveland. His series, Precious Objects will next be seen at the Butler Institute of Art in June 2013.

The Album Project

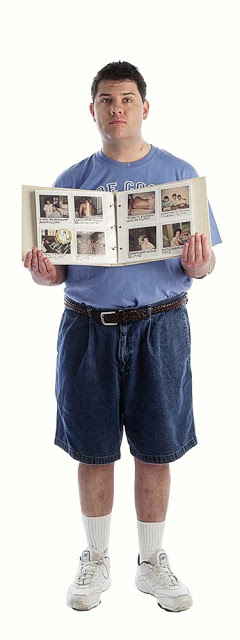

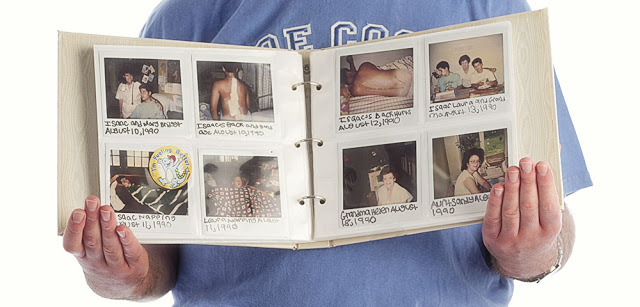

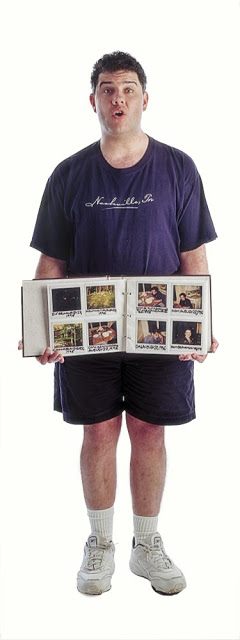

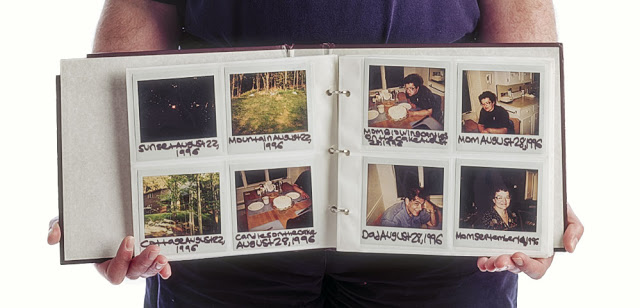

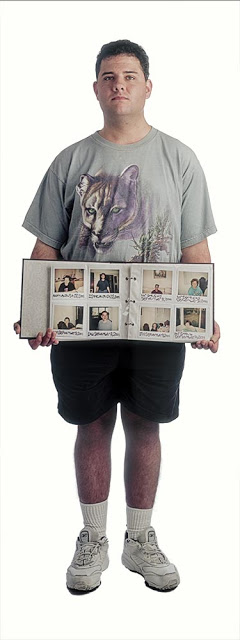

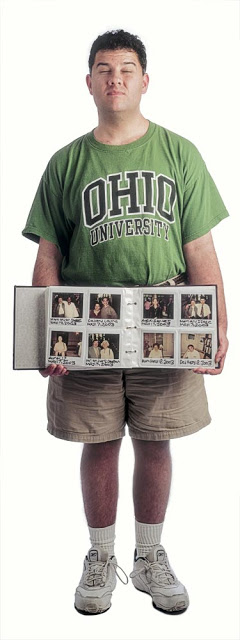

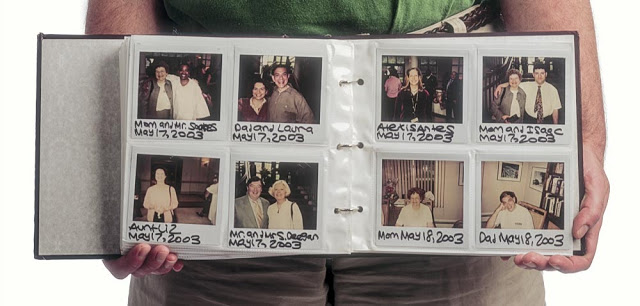

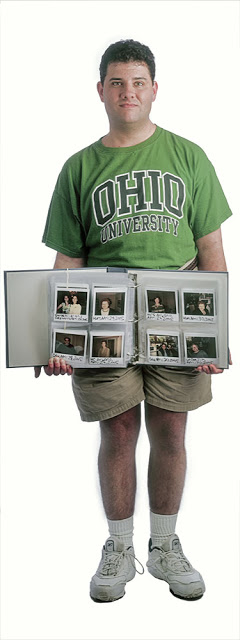

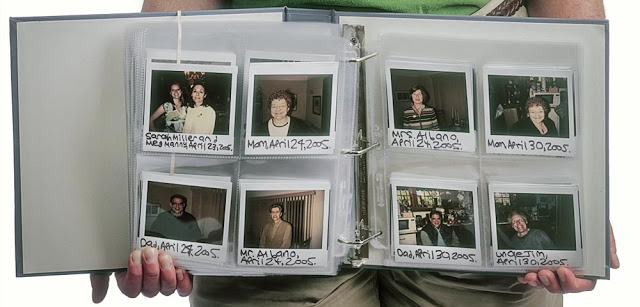

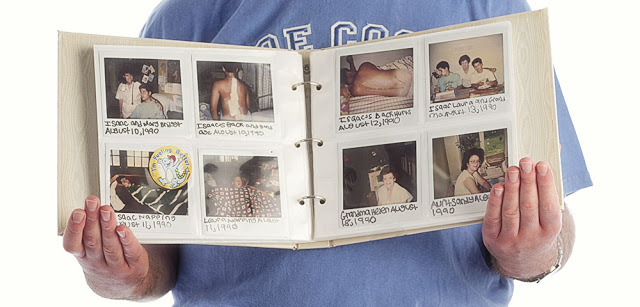

Around the time of his fifteenth birthday in 1990, our son Isaac developed a serious curvature of his spine. Isaac has autism – a limited ability to communicate. In an attempt to help him understand the surgery, we bought him a Polaroid Spectra camera. We hoped to use it to show him what was happening. Somewhat to our surprise, the camera became his constant companion at family events – a tool for him to order his world.

This project is a record of Isaac and his photographs. The five-hour scoliosis surgery, so intimidating at the time, becomes no more than the background for this story. The story is his ability to overcome his limitations and build a life independent from his parents. It is a history and a tribute to the family members and friends, many of whom are no longer with us that live in his albums. But, that is not why I did it. The project is about telling your story with a limited palette – language, both verbal and written – body language – photographs. It is about the discomfort and frustration of using every tool you have and still not being understood. It is at the heart of Isaac’s disability but a shared frustration for us all.

When exhibited, these images are printed large 24”x64”. This allows the Polaroids to be seen as they should be but the large cutout figures can be disturbing. There is a tendency to romanticize these albums as self-expression. We have no evidence of that. We don’t know what they mean to him. That is the core of the message. We need to accept that others see things differently than we do without trying to fit them in our mold. It is called respect.

I struggled for a long time trying to understand why Isaac so enjoyed doing this project with me. He does not naturally like to stand still or take detailed directions on how to hold things. Since he cannot really tell why he was so comfortable, we can only guess. A trap with him is that he frequently is comfortable doing something he has done before. No secret, he likes repetition. But, this was different – he took to it from the start. I finally realized what was going on. He and I were collaborating.

Every Place – I have ever lived

The foreclosure crisis in 12 neighborhoods

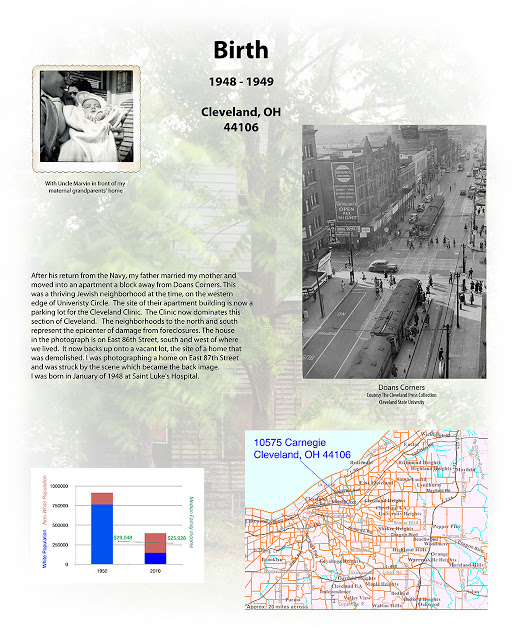

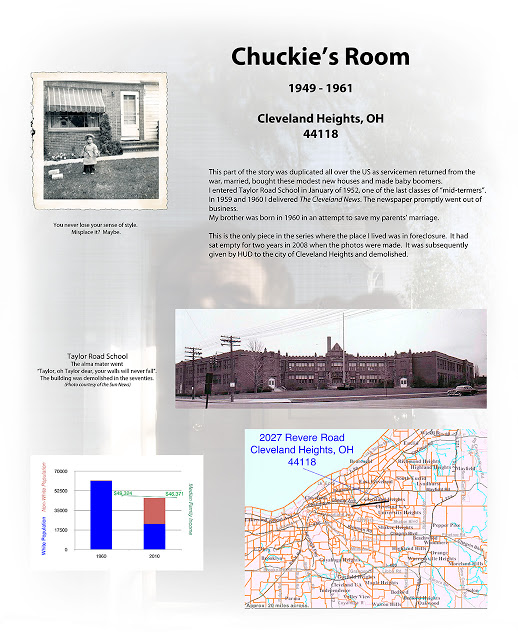

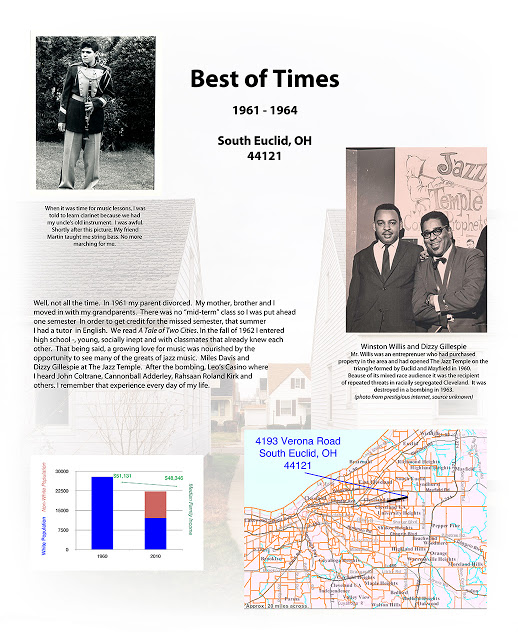

The pieces in this project each contain images of a foreclosed home in the 12 neighborhoods I’ve lived in. Many were built after wars, in times of what seemed like, boundless economic growth. Home ownership had become symbolic of The American Dream.

Each work is a 4’ x 4’ sheet of raw plywood with two photographs that are printed on fabric. The “inside” photograph is screwed in place. The top image has been made into a window shade that pulls down over the first.

The second and the twelfth pieces were made for a group exhibition at Cleveland Public Art in 2008. The second piece, my childhood home, is the only one in the series where I actually lived in the home.

Sidepieces for each location briefly explain both where the piece fits into my personal biography and provide some information about the neighborhood portrayed.

Maps on the sidepieces show where you are in my personal journey. In addition, there are charts of both the changes in median family income between when the time I lived there and now (based upon the 2000 census) and the changes in racial mix between then and now (based upon the 2010 census).

You cannot tell this story without considering changes in population, race and economics.

Every project I undertake is a journey that reveals its meaning as it is assembled. In Every Place, the original concept was to show how this crisis reaches beyond the very poor and is, in fact, a problem for all of us. This certainly proved to be true. It seems in this series that there are three crises.

There were fine homes that appeared to have been owned by people of means.

In neighborhoods that would, at one time, have been called “blue collar”, it was not the same. Here, it was easy to find multiple foreclosed homes on a street. Curiously, the streets in these neighborhoods still looked intact. Lawns were mowed; properties were in decent shape.

In the inner city it was different. No search on the Internet to find these places was necessary. A drive down any of the side streets in the neighborhoods south and north of my parents’ apartment yielded a stream of boarded up properties punctuated by now empty lots. It was clear that efforts had been made in some of these places to keep things together, and the other homes on the street that are occupied were in good shape. In fact, there was mixed-in some relatively new construction – it looked a bit like a forest after a fire as plants begin to reestablish. It is, however, a mistake to be fooled by this optimism. What happened is horrible and has not ended.

In the end, I just don’t know what to think. When I visited the site of my childhood home a few weeks ago, it had been torn down. It was disturbing. You expect these things to age and change, maybe deteriorate. But disappear?

This feels like a war on the idea of the family home. It is easy to see who lost. I have no idea who won.

This project has been installed three times and will at the Cleveland State University College of Urban Affairs Campbell Gallery in September 2013 and at the Wilmington College Gallery in January 2014