Kirk Crippens

I was in the midst of a long process of photographing portraits inside San Quentin in May 2011 when the Supreme Court declared the overcrowding in California’s prison system unconstitutional and ordered the population lowered by 133,000 to achieve 137.5% capacity. My project began in 2008, when I petitioned the prison to allow me inside with my cameras. A year and a half later I was granted limited access and began a series of brief one-hour visits with the men. I was allowed inside once a year between 2009-12.

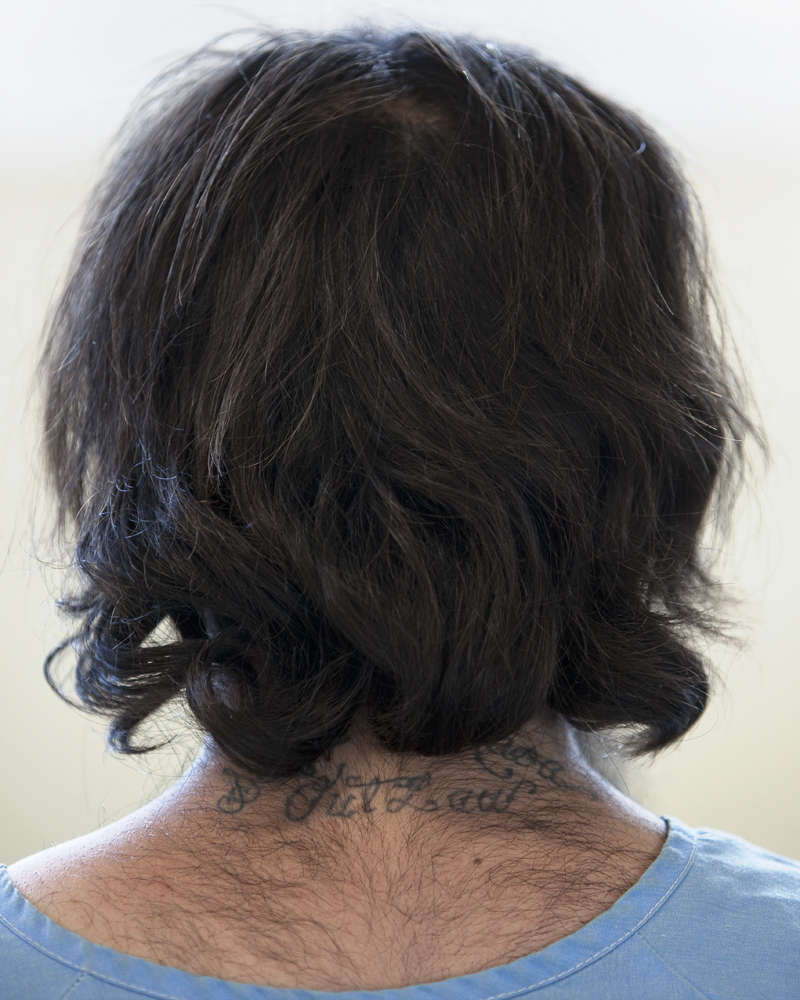

When invited back in January 2012, I decided to try a different approach that included bringing a tripod and directly asking the men to pose for me. I set up my tripod in front of a cinder block wall in the San Quentin cafeteria and began asking the men if I could take their portrait. Most seemed honored; a few declined. It wasn’t how the guards or warden expected me to work, and I could feel the tension. The guards whispered and huddled together in the corner. Less than an hour later they asked me to leave and ushered me out. Although the series I’m submitting feels complete, I continue to be interested in prison culture and the political issues affecting it. I hope to visit again.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026